Decorated for Christmas, it’s warm and cozy. Now then, imagine that over to the righthand side of the fireplace, there sits a man in a large armchair. He’s not a handsome man by any means, but his face is strongly marked by intelligence and humor—and he is about to work magic.

All stories are magic, but there are some that gain in the telling by being read aloud. So imagine, also, a group of students—all male, for this man is provost of a famous British preparatory school—seated in chairs or on the floor, coltish legs and sharp elbows pulled in, anticipating wonders.

We owe the tradition of telling ghost stories at Christmas mainly to Charles Dickens. Dickens’s most famous work in the genre, A Christmas Carol, is subtitled Being a Ghost Story of Christmas. Dickens, as editor of various magazines in the course of his career, always put out a Christmas annual which consisted in the main of ghost stories, by some of the most famous writers of his day: Wilkie Collins, Elizabeth Gaskell, Amelia B. Edwards, and of course Dickens himself.

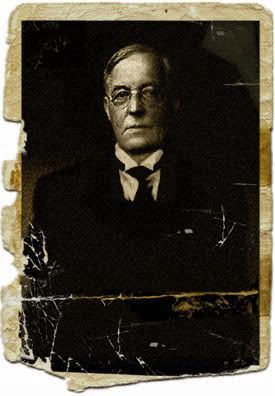

The man who is about to read to his students, however, was born too late to submit his stories to Dickens. Montague Rhodes James is, however, arguably the finest of all writers of fictional ghost stories.

Born the youngest son of a Sussex clergyman in 1862, he was also one of the unlikeliest. By profession a historian (mainly of medieval England), he lived out his life a bachelor, first as a Cambridge University chancellor and, for the last eighteen years of his life as provost of Eton. There would seem to be nothing in his background to account for his taste for the macabre.

In his spare time, however, he wrote ghost stories. At first he read them to his fellow Cambridge dons during the Christmas season; later, for his pupils at Eton.

In our own day, we are used to writers in the horror genre who use bloody menaces—serial killers, killer clowns, demons, rabid dogs, kinetically gifted teens (yes, Stephen King, I’m primarily, but not solely, talking about you)—to scare us witless. Not once does M. R. James resort to this type of over-the-top plotline, or, in King’s evocative phrase, go for the gross-out, yet James’s stories can scare one into turning on extra lights, and checking dark corners, strictly by the power of suggestion. In the preface to a collection of his stories called A WARNING TO THE CURIOUS AND OTHER STORIES, the author Ruth Rendall—herself no mean hand at creating uncanny atmospheres—gives a near perfect description of how James achieves these scares:

"His stories begin quietly, often with a description of a place, a town or a country house or library, and his traveller to whom in a little while dreadful things will happen. There are—at first—no ghosts and demons, only a gradually increasing, indefinable, slow menace. And James’s characters bring trouble on themselves by such simple innocent actions, by being a little too curious, by merely examining an old manuscript or borrowing a certain book, by picking up an apparently harmless object on the beach." (pages vii-viii.)

The stories to which Rendall refers, in that final sentence, are, respectively, "A Warning to the Curious", " Canon Alberic's Scrapbook" and "The Tractate Middoth," and "O Whistle and I’ll Come to You, My Lad", but the general idea holds true for all of James’s stories. Not to mention that these stories have influenced a good many writers—even Stephen King—who came after James; there is a scene in King’s 1977 novel The Shining that must have been inspired by one in James’s early story "Lost Hearts", in which a young boy is frightened by a ghastly figure he sees in a bathtub.

It is astonishing, as well, that James’s influence should have spread so far when his output in the genre consists of no more than thirty-one short stories.

I suspect, though, that one thing that makes them so memorable is, simply, that James himself first read them aloud—and he must have been a wonderful reader, for none of the fellow professors or students who heard him read them at Christmastime ever forgot them. At least one of his pupils, the English actor Christopher Lee, has read James’s work on BBC radio, and shared his memories of hearing "Monty" in his youth. (James died in 1936.)

I frankly cannot do any sort of justice to James’s work; my powers of description aren’t equal to the task. However, his best stories are available online. These two are my favorites.

Lost Hearts

A Warning to the Curious

These will give you a savor of M. R. James’s variety of dark magic.

I've never heard of Mr. James but his stories sound like something that would be right up Amanda's alley what with her love of ghost stories and such. I'll have to point her in the direction of the stories that you've linked to and have her check them out. I believe I'll take a gander myself, too, as you've got me quite curious and I do love the occasional ghost story!

ReplyDeleteThanks for posting the links Fairweather. Right now its a little too early and dark to read James' work. Maybe around noon today, when the sun is as high in the sky as its likely to get this time of year, I'll risk coming back for a read.

ReplyDeleteHi Linda--sorry to be so long answering! I think Amanda will love MRJ's work. He can set up an atmosphere like nobody else--and then deliver a genuine scare without, as Stephen King says, going for the grossout. Other good ones to check out would be "Count Magnus" (probably the most frightening in the bunch) and, for Amanda, with her talent in art (I've been reading your blog for some time, just haven't commented much--since Jamie sent me an email with your blog URL) "The Mezzotint", which is about an old, old etching that behaves very strangely.

ReplyDeleteYou got that right, Barry. Much less scary to read his work in bright light, with no shadows in the corners.:)

ReplyDelete